Colonial-Period Archaeological Site Discovered at Jug Bay

Archaeologists with Anne Arundel County’s Cultural Resources Section have uncovered a previously unknown 17th-century archaeological site in Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in southwest Anne Arundel County, Maryland. The discovery was announced at a public event at Jug Bay on May 14th by C. Jane Cox, Chief of Cultural Resources for Anne Arundel County.

Anne Arundel County, in collaboration with the nonprofit organization the Lost Towns Project, has been exploring archaeological sites within and around the County-owned Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary since the early 2000s. Along the Jug Bay segment of the Patuxent River there are nearly 80 unique archaeological sites recorded. The sites range in type and time period, representing a unique continuity of human habitation from the earliest sites, dating to 13,000 years old, through the European arrival of ca. 1650, and on to the present day. Work is largely supported by competitive research grants, and the labor-intensive work of archaeology is supplemented by the incredible contributions of volunteers. Our citizen science based model has, over the past 30 years, resulted in intensive excavations of nearly 200 sites across the County.

In early 2019, the archaeology crew discovered a new site, now named Pindell Bluff (18AN1672), as part of a state grant-funded project to survey and document archaeological sites around Jug Bay and to assess how natural processes like sea level rise and climate change might be affecting the archaeological record. Excavations in the summer of 2019, as part of a field school with Washington College led by Dr. Julie Markin, produced a rich variety of native-period artifacts, including a rare Clovis Point dating to up to 13,000 years ago. Between the prehistoric ceramics, projectile points, and occasional burnt animal bones the team would occasionally find a tiny fragment of historic-period pottery or deteriorated iron nails. However, the intensity of the prehistoric material overshadowed those small hints that people were also in this same space during the historic period.

In 2020, and with volunteer assistance, the crew conducted a systematic metal detector survey on the perimeter of the site and uncovered the blade of a broad hoe dating to ca. 1680-1700. Unfortunately, after this discovery, the pandemic hit and all work was put on hold. The crew was able to return in April 2021 to finish the last few excavation units and conduct one final shovel test pit survey before closing the site for the season. On the final day of the project, the crew, led by Shawn Sharpe and Drew Webster, alongside volunteers Barry Gay, Kevin McCurley, and Dani Tafolla, encountered several shovel test pits with high concentrations of colonial-era artifacts. The survey definitively showed that there had been a domestic occupation of this same bluff sometime between 1670-1730. Diagnostic artifacts included English and German ceramics dating to the late 17th and early 18th centuries as well as clay tobacco pipes from the same period.

This discovery marks the earliest confirmed colonial-period site at Jug Bay, and is among the earliest historic sites in Anne Arundel County! Of the more than 1,700 recorded archaeological sites in the county, only 23 are historic sites that predate 1700. Most of those are located along the Chesapeake Bay shoreline. This site has the potential to tell us about a much less understood period of history; the first generation of people who settled Anne Arundel County along the Patuxent River.

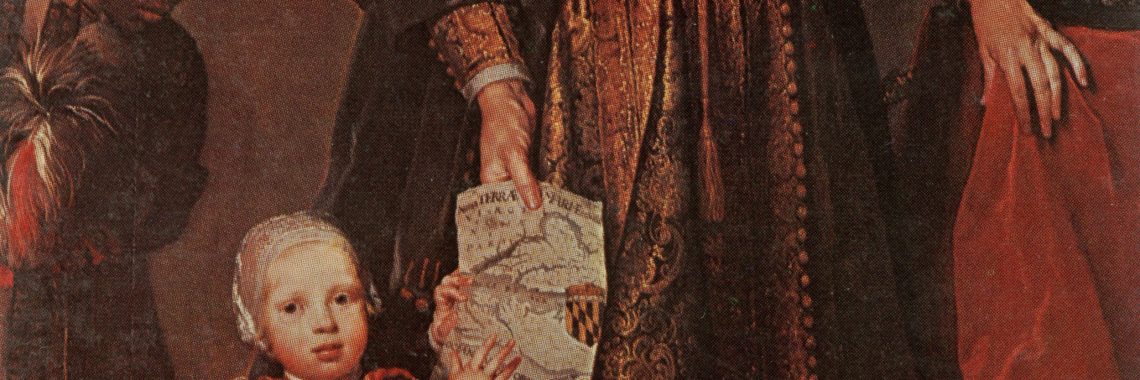

Permanent European settlement in Anne Arundel County began in earnest in 1649, when 300 settlers–landowners, families, indentured servants, and later, enslaved Africans–arrived from St Mary’s City and Southeast Virginia to start a new settlement they called Providence along the Severn River and in the Broadneck peninsula area. Soon the European population spread across lands in the West River area and on Herring Bay. From those first 300 settlers, the population grew, and across all of the colony, historians estimate that there were about 33,000 people living in Maryland by 1680. Who might have been living at Pindell Bluff?

Archival research by Pat Melville and Dave Linthicum shows that the 300-acre property was first patented by Ninial Beall and called “Bachelors Choice” in 1669. While Beall first arrived in Maryland as an indentured servant, serving a Richard Hall of Calvert County for five years, he did not arrive in quite the same fashion as most other indentured servants. The Scotsman was captured by Oliver Cromwell’s forces at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650, and transported to Barbados as a prisoner. He was sent to Calvert County, MD in 1655, and placed with Richard Hall to serve out his sentence.

While Beall owned the property, records indicate that he likely never lived there. By sponsoring new settlers to Maryland colony, Beall was granted over 4,000 acres of land by the time he passed in 1717. Initial research uncovered two leases associated with the parcel of land, from 1702 and 1704,that suggest the land was owned by Jonas Jordan, a carpenter, and his wife Mary and son Thomas. It is possible that the Jordan family lived on the land in the late 17th century, until Jonas Jordan passed away. By 1702, Mary Jordan had remarried and leased all of Bachelors Choice to Seth Biggs, a tobacco planter and merchant. Court cases suggest he was living near the Western Branch of the Patuxent between 1680 and 1698, thus making him a likely suspect for our site’s resident. Biggs died without an heir in 1711. Combined with information from the artifacts, this archival research places the likely occupation of the site between 1680 and 1710.

This is just the beginning of research on the property. The cultural resources team has begun exploring research grant opportunities to fund more work, and plans to reach out to our partners at area colleges to see if there is interest in a future academic field school. The goal is for this site to become a project where interested citizens can participate through the County’s Preservation Stewardship Program, which encourages local citizens, students, and scholars to get involved in exploring local history. To learn more about Anne Arundel County Cultural Resources Section or get involved, visit aacounty.org/cr