What is an Internship with the Lost Towns Project Like?

We asked Catonsville High School senior and 2022 intern Abby Shackelford. Here is what she had to say:

I first discovered the Lost Towns Project in a Maryland Archaeology Month pamphlet I picked up while on a college tour at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. Originally, I had hoped to find something closer to home, but as I looked through the pamphlet, I realized that Anne Arundel County was as close as I was going to get. I applied for the internship because I wanted to make sure that I liked archaeology and got some experience with it before I chose to pursue it in college.

I really enjoyed our field trips to all of the different sites. It was cool to see how they varied in upkeep and the difficulties that the different environments caused while executing field work. I also enjoyed the trip to the Prince George’s County Archaeology Lab because it was interesting to see the difference in collections storage from county to county, and it was cool to see how other people did their processing and cataloging procedures outside of our tiny sphere at the London Town Lab. I liked how we had an equal balance of lab days and field days. It was good to have some variety, and I really enjoyed all of the field trips to all sorts of cool historical sites I wouldn’t otherwise have heard about. Conversely, it was also nice to have the lab days after weeks out in the field, sweating in the heat. Some days you just needed to sit and mindlessly clean some brick with a toothbrush while you soaked up some AC.

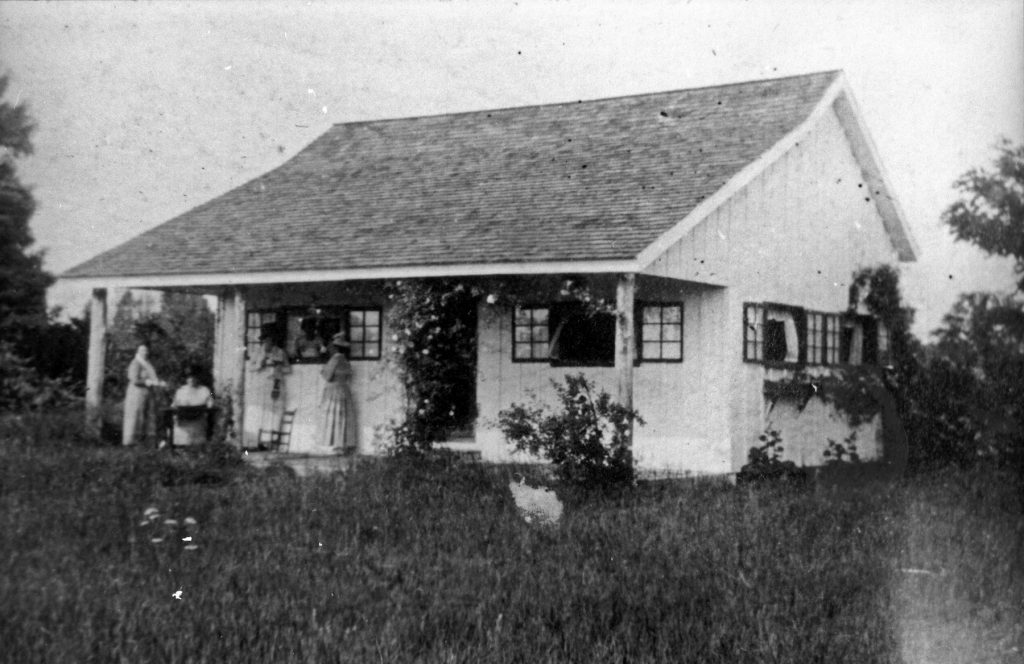

Altogether, besides miscellaneous lab work, I worked on two major field projects. One was at Kinder Farm, while one was at Arden. Kinder Farm Park, an Anne Arundel County park, was formerly the site of the Kinder family farm. The Kinders were German immigrants and truck farmers, growing produce and transporting it to larger centers of commerce for sale. We dug multiple shovel test pits (STPs) around the locations of two of the major farmhouses and other various outbuildings, finding a variety of artifacts, mostly from the early 20th century.

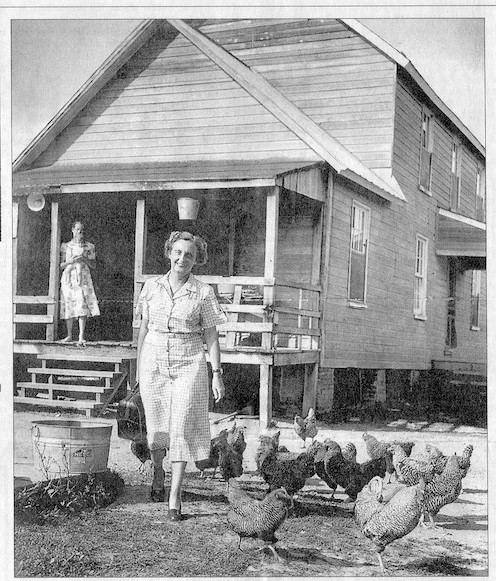

Our other major field project was on a private property—a former plantation known as Arden, built in the 1840s. Arden was home to Dr. James Murray, a slaveholder, who served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War as a surgeon. We excavated in the woods near the main house, around and in the foundation of a former tenant house, where a man we know only by oral retelling as “Uncle Wec,” reportedly a former slave on the plantation, lived up until the 1940s. We collected surface finds, dug STPs around the remains of the foundation, and excavated a unit in the corner of the house. Most of the artifacts we found likely dated to the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

A memorable moment would be when I dropped my phone in poison ivy. The worst part was that we weren’t even in the field! I dropped it off of the deck by the waterfront and it managed to land face down on the one patch of poison ivy in the whole garden (but luckily it missed the storm drain which was mere inches away). Before this internship, I had no idea what poison ivy looked like. I knew it had three leaves and it was shiny, but I didn’t know its exact appearance. I can now confidently say I know what it looks like. It just took dropping my phone in it and getting a little bit of it on my hand for me to figure it out.

I would definitely recommend this internship to other students. For another high school student, I think this internship could also be helpful to help them determine whether or not they want to continue with archaeology as a career path, since it was composed of a wide array of everyday archaeological tasks. My main takeaway from this internship would have to be that I learned methods of archaeology—I gained experience in different techniques used to clean, label, and excavate artifacts, among other things. I think I can also claim to know the layout of the lab pretty well, after all of the cleaning and organizing we did of it. Coming away from this internship, I can now say that I have more of an idea of what I am getting into if I choose to pursue archaeology as a profession. The hands-on experience that this internship has afforded me has been invaluable. I have had opportunities in the archaeology world that I would not have otherwise had if not for this internship, such as the opportunity to observe ground-penetrating radar, help organize and store collections, and go on “behind the scenes” tours of museums like the Mt. Calvert House and the exhibits at London Town. I am also doubly as grateful to have these opportunities as a high schooler who had no prior experience with archaeology coming in to the internship. Having completed this internship has also hopefully given me a leg up in the college application process, which is fast approaching for me, as it is yet another extracurricular to add to my application. This internship has been an experience that not many high schoolers often get.

Overall, this internship was a very great experience for me. I was very lucky to get the opportunity to do it, and I had a lot of fun this summer. This internship has only solidified my desire to continue to do archaeology. I am planning to continue volunteering at the lab every now and then during the upcoming school year. I look forward to being able to expand my knowledge of history and archaeology.