Native American Heritage and Archaeology

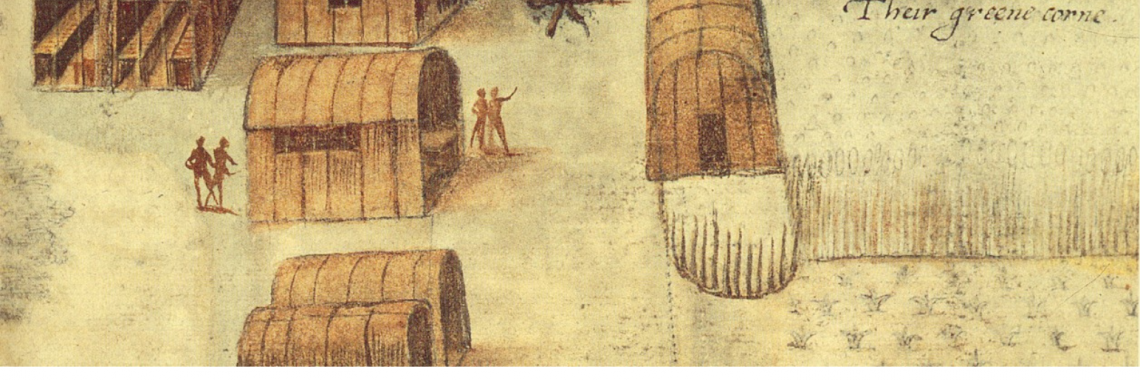

A new educational toolbox highlighting 13,000 years of indigenous presence in Anne Arundel County

The Lost Towns Project, Inc., in collaboration with archaeologists with the County’s Cultural Resources Section, is proud to announce the launch of “Native American Archaeology in Anne Arundel County, Maryland: A Heritage Toolbox.” Designed for students, teachers, and the curious public, this virtual toolbox shares exciting local archaeological discoveries, along with images of artifacts from the County’s vast archaeological holdings that have helped document and reveal the deep history of indigenous peoples in what is today known as Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

Visit losttownsproject.org/toolbox to explore 13,000 years of indigenous history, learn more about fascinating archaeological resources across the County, download valuable educational resources, and find places where you can visit and experience this history in person!

Funded in part by the Chesapeake Crossroads Heritage Area in recognition of the lack of publicly available resources available that tell of the County’s rich indigenous history, the toolbox provides historical context, along with multimedia resources, including interviews with members of local tribes and professional archaeologists, images of artifacts excavated from across the county, and links to presentations by academic experts, web resources, worksheets, and videos. It also showcases the rich archaeological discoveries from the Jug Bay area, a tidal wetland along the Patuxent River in southwest Anne Arundel County.

Dr. Patricia Delgado, Superintendent and Wetland Ecologist at Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Lothian, MD welcomes new visitors to the Sanctuary to immerse themselves in the natural environment, and explore the lands where Native peoples once lived. She notes that “the addition of a website dedicated to presenting the Native American story of Jug Bay provides a permanent and accessible way to share these important aspects of our local heritage with the public.” Plan your visit at www.jugbay.org!

Eve Case, Coordinator of Social Studies at Anne Arundel County Public Schools (AACPS) sees the toolbox as “an important resource for social studies teachers looking to incorporate local history into their curricula,” adding that “Native American history is a subject area for which we have few local resources on hand.”

Drew Webster, archaeologist and the County’s Historic Preservation Stewardship Program Director, designed the toolbox with the hope that teachers could use the digital toolbox to broaden their curricula, build new lesson plans, and encourage their students to research and explore the area’s extensive indigenous heritage, both virtually and in person.

Mr. Webster also invites the public to experience archaeology firsthand! Sign up for a monthly newsletter by emailing volunteers@losttownsproject.org and be first to know about volunteer opportunities in the field and the lab, and to hear about new exhibits and lectures about Native American history and archaeology in 2023.

Learn more about the non-profit Lost Towns Project at www.losttownsproject.org, and explore the County’s many other historic resources by visiting www.aacounty.org/heritage-resources.